John Henry Patterson (author) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Henry Patterson (10 November 1867 – 18 June 1947), known as J. H. Patterson, was an Irish member of the

/ref>

Almost immediately after Patterson's arrival, lion attacks began to take place on the workforce, with the lions dragging men out of their tents at night and feeding on their victims. Despite the building of thorn barriers ('' bomas'') around the camps, bonfires at night, and strict after-dark curfews, the attacks escalated dramatically, to the point where the bridge construction ceased due to a fearful, mass departure by the workers. Along with the obvious financial consequences of the work stoppage, Patterson faced the challenge of maintaining his authority and even his personal safety at this remote site against the increasingly hostile and superstitious workers, many of whom were convinced that the lions were in fact evil spirits, come to punish those who worked at

Almost immediately after Patterson's arrival, lion attacks began to take place on the workforce, with the lions dragging men out of their tents at night and feeding on their victims. Despite the building of thorn barriers ('' bomas'') around the camps, bonfires at night, and strict after-dark curfews, the attacks escalated dramatically, to the point where the bridge construction ceased due to a fearful, mass departure by the workers. Along with the obvious financial consequences of the work stoppage, Patterson faced the challenge of maintaining his authority and even his personal safety at this remote site against the increasingly hostile and superstitious workers, many of whom were convinced that the lions were in fact evil spirits, come to punish those who worked at  The workers and local people immediately declared Patterson a hero, and word of the event quickly spread far and wide, as evidenced by the subsequent

The workers and local people immediately declared Patterson a hero, and word of the event quickly spread far and wide, as evidenced by the subsequent

In 1906, Patterson returned to the Tsavo area for a hunting trip. During the trip, he shot an eland, which he noted possessed different features from elands in Southern Africa, where the species was first recognized. On returning to England, Patterson had the head of the eland mounted, where it was seen by

In 1906, Patterson returned to the Tsavo area for a hunting trip. During the trip, he shot an eland, which he noted possessed different features from elands in Southern Africa, where the species was first recognized. On returning to England, Patterson had the head of the eland mounted, where it was seen by

During his time in command of the Jewish Legion (which served with distinction in the Palestine Campaign), Patterson was forced to deal with extensive, ongoing

During his time in command of the Jewish Legion (which served with distinction in the Palestine Campaign), Patterson was forced to deal with extensive, ongoing

During the 1940s, Patterson and his wife, "Francie", lived in a modest home in

During the 1940s, Patterson and his wife, "Francie", lived in a modest home in Israel Philatelic Service Bulletin, No. 68, January 2015, page 4

/ref>

''In the Grip of the Nyika; Further Adventures in British East Africa''

London: Macmillan and Co., 1909

''With the Zionists in Gallipoli''

London: Hutchinson, 1916

''With the Judaeans in the Palestine Campaign''

London: Hutchinson, 1922

British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

, hunter, author and Christian Zionist, best known for his book ''The Man-Eaters of Tsavo

''The Man-Eaters of Tsavo'' is a semi-autobiographical book written by British soldier and author John Henry Patterson. Published in 1907, it recounts his experiences in East Africa while supervising the construction of a railroad bridge over the ...

'' (1907), which details his experiences while building a railway bridge over the Tsavo River

The Tsavo River is located in the Coast Province in Kenya. It runs east from the western end of the Tsavo West National Park of Kenya, near the border of Tanzania, until it joins with the Athi River, forming the Galana River near the center of t ...

in British East Africa

East Africa Protectorate (also known as British East Africa) was an area in the African Great Lakes occupying roughly the same terrain as present-day Kenya from the Indian Ocean inland to the border with Uganda in the west. Controlled by Bri ...

(now Kenya) in 1898–1899. The book has inspired three Hollywood films: ''Bwana Devil

''Bwana Devil'' is a 1952 American adventure B movie written, directed, and produced by Arch Oboler, and starring Robert Stack, Barbara Britton, and Nigel Bruce. ''Bwana Devil'' is based on the true story of the Tsavo maneaters and filmed wit ...

'' (1952), ''Killers of Kilimanjaro

''Killers of Kilimanjaro'' is a 1959 British CinemaScope adventure film directed by Richard Thorpe and starring Robert Taylor, Anthony Newley, Anne Aubrey and Donald Pleasence for Warwick Films.

The film was originally known as ''Adamson of A ...

'' (1959) and ''The Ghost and the Darkness

''The Ghost and the Darkness'' is a 1996 American historical adventure film directed by Stephen Hopkins and starring Val Kilmer and Michael Douglas. The screenplay, written by William Goldman, is a fictionalized account of the Tsavo man-eaters, ...

'' (1996).

In the First World War, Patterson was the commander of the Jewish Legion

The Jewish Legion (1917–1921) is an unofficial name used to refer to five battalions of Jewish volunteers, the 38th to 42nd (Service) Battalions of the Royal Fusiliers in the British Army, raised to fight against the Ottoman Empire during ...

, "the first Jewish fighting force in nearly two millennia", and has been described as the godfather of the modern Israel Defense Forces

The Israel Defense Forces (IDF; he, צְבָא הַהֲגָנָה לְיִשְׂרָאֵל , ), alternatively referred to by the Hebrew-language acronym (), is the national military of the Israel, State of Israel. It consists of three servic ...

.Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu's Remarks at the Burial Ceremony for Lt. Col. John Henry Patterson's Ashes; 4 December 2014/ref>

Biography

Youth and Army service

Patterson was born in 1867 inForgney

Forgney () is a civil parish and townland in County Longford, Ireland. Evidence of ancient settlement in the area include a number of ringfort and holy well sites in Forgney townland.

Forgney is associated with the poet Oliver Goldsmith, and ...

, Ballymahon

Ballymahon () on the River Inny is a town in the southern part of County Longford, Ireland. It is located at the junction of the N55 National secondary road and the R392 regional road.

History

Ballymahon derives its name from the Irish lang ...

, County Longford

County Longford ( gle, Contae an Longfoirt) is a county in Ireland. It is in the province of Leinster. It is named after the town of Longford. Longford County Council is the local authority for the county. The population of the county was 46,6 ...

, Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

, to a Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

father and Roman Catholic

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*'' Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a lette ...

mother.

He joined the British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

in 1885 at the age of seventeen and eventually attained the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colonel. ...

and was awarded the Distinguished Service Order

The Distinguished Service Order (DSO) is a military decoration of the United Kingdom, as well as formerly of other parts of the Commonwealth, awarded for meritorious or distinguished service by officers of the armed forces during wartime, typ ...

(DSO). He retired from the army in 1920.

East African adventures

In 1898, Patterson was commissioned by theUganda Railway

The Uganda Railway was a metre-gauge railway system and former British state-owned railway company. The line linked the interiors of Uganda and Kenya with the Indian Ocean port of Mombasa in Kenya. After a series of mergers and splits, the lin ...

committee in London to oversee the construction of a railway bridge over the Tsavo River

The Tsavo River is located in the Coast Province in Kenya. It runs east from the western end of the Tsavo West National Park of Kenya, near the border of Tanzania, until it joins with the Athi River, forming the Galana River near the center of t ...

in present-day Kenya

)

, national_anthem = "Ee Mungu Nguvu Yetu"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, image_map2 =

, capital = Nairobi

, coordinates =

, largest_city = Nairobi

, ...

. He arrived at the site in March of that year.

Tsavo railway and man-eaters

Almost immediately after Patterson's arrival, lion attacks began to take place on the workforce, with the lions dragging men out of their tents at night and feeding on their victims. Despite the building of thorn barriers ('' bomas'') around the camps, bonfires at night, and strict after-dark curfews, the attacks escalated dramatically, to the point where the bridge construction ceased due to a fearful, mass departure by the workers. Along with the obvious financial consequences of the work stoppage, Patterson faced the challenge of maintaining his authority and even his personal safety at this remote site against the increasingly hostile and superstitious workers, many of whom were convinced that the lions were in fact evil spirits, come to punish those who worked at

Almost immediately after Patterson's arrival, lion attacks began to take place on the workforce, with the lions dragging men out of their tents at night and feeding on their victims. Despite the building of thorn barriers ('' bomas'') around the camps, bonfires at night, and strict after-dark curfews, the attacks escalated dramatically, to the point where the bridge construction ceased due to a fearful, mass departure by the workers. Along with the obvious financial consequences of the work stoppage, Patterson faced the challenge of maintaining his authority and even his personal safety at this remote site against the increasingly hostile and superstitious workers, many of whom were convinced that the lions were in fact evil spirits, come to punish those who worked at Tsavo

Tsavo is a region of Kenya located at the crossing of the Uganda Railway over the Tsavo River, close to where it meets the Athi-Galana-Sabaki River. Two national parks, Tsavo East and Tsavo West are located in the area.

The meaning of the w ...

, and that he was the cause of the misfortune because the attacks had coincided with his arrival.

The man-eating behaviour was considered highly unusual for lions and was eventually confirmed to be the work of a pair of rogue males, who were believed to be responsible for as many as 140 deaths. Railway records attribute only 28 worker deaths to the lions, but the predators were also reported to have killed a significant number of local people of which no official record was ever kept, which attributed to the railway's smaller record.

Various theories have been put forward to account for the lions' man-eating behaviour: poor burial practices, low populations of food source animals due to disease, etc. There was a slave trade

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

route through the area, which contributed to a considerable number of abandoned bodies. Patterson reported seeing considerable instances of unburied human remains and open graves in the area, and it is believed that the lions (which, like most predators, will readily scavenge

Scavengers are animals that consume Corpse decomposition, dead organisms that have died from causes other than predation or have been killed by other predators. While scavenging generally refers to carnivores feeding on carrion, it is also a h ...

for food) adapted to this abundant, accessible food supply and eventually turned to humans as their primary food source. A modern analysis shows one of the lion's skulls had a badly abscess

An abscess is a collection of pus that has built up within the tissue of the body. Signs and symptoms of abscesses include redness, pain, warmth, and swelling. The swelling may feel fluid-filled when pressed. The area of redness often extends b ...

ed canine tooth that could have hindered normal hunting behaviour. However, this hypothesis accounts for the behaviour of only one of the lions involved, and Patterson himself had disclaimed such theories, saying he had damaged the lion's tooth himself.

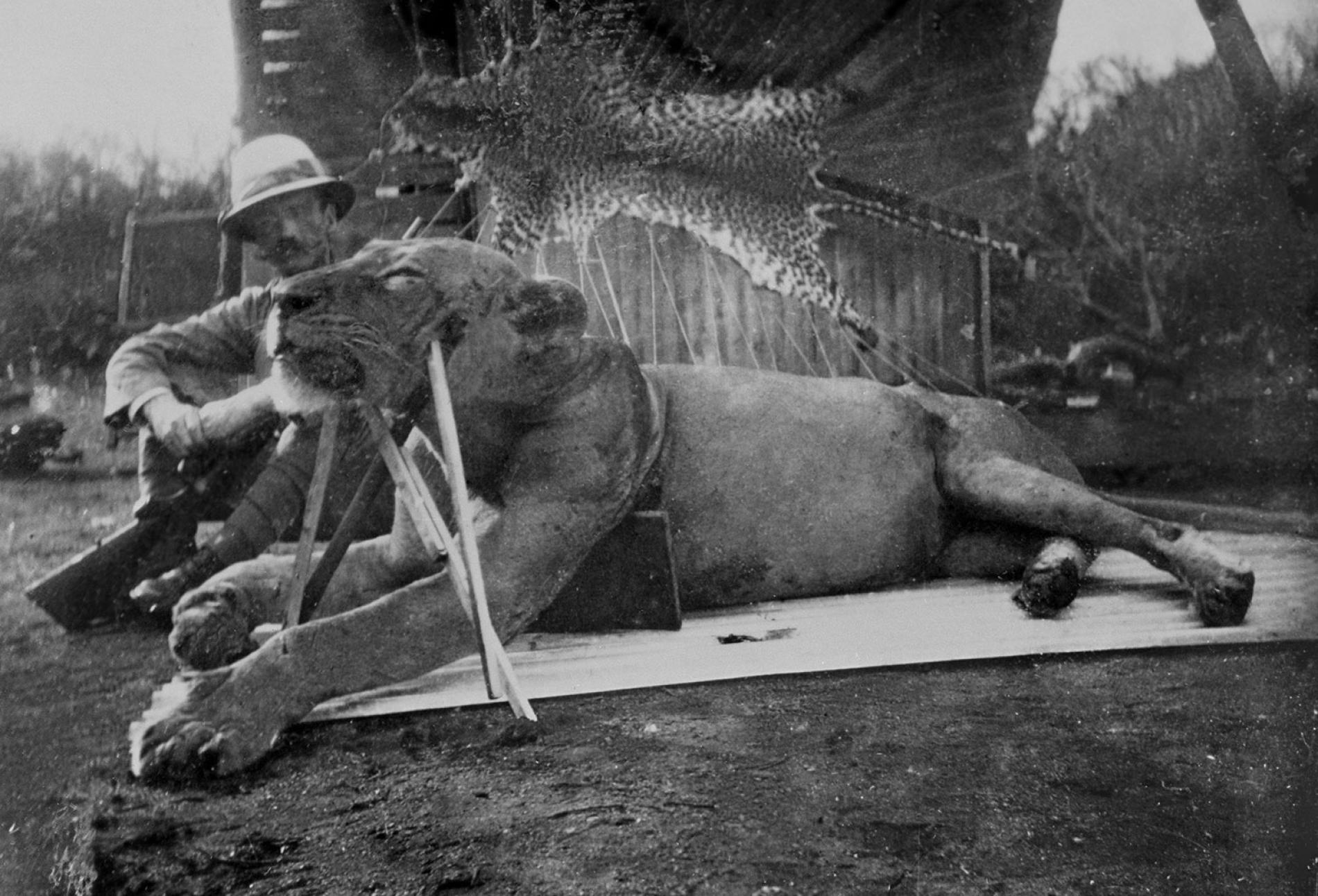

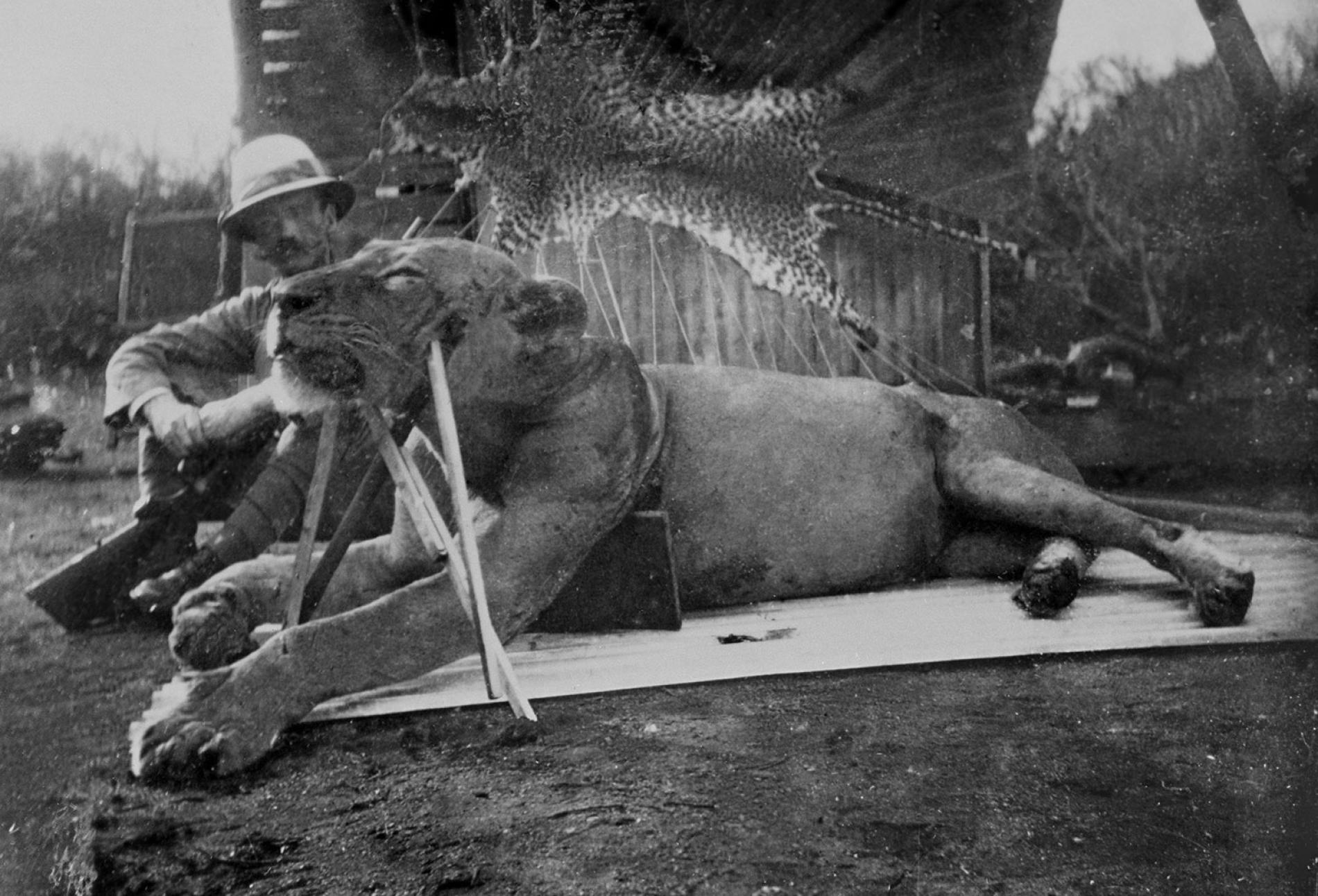

With his reputation, livelihood, and safety at stake, Patterson, an experienced tiger hunter from his military service in India, undertook an extensive effort to deal with the crisis. After months of attempts and near misses, he killed the first lion on the night of 9 December 1898 and the second one on the morning of 29 December (narrowly escaping death when the wounded animal charged him). The lions were maneless like many others in the Tsavo area, and both were exceptionally large. Each lion was over nine feet long from nose to tip of tail and required at least eight men to carry it back to the camp.  The workers and local people immediately declared Patterson a hero, and word of the event quickly spread far and wide, as evidenced by the subsequent

The workers and local people immediately declared Patterson a hero, and word of the event quickly spread far and wide, as evidenced by the subsequent telegrams

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas p ...

of congratulations he received. Word of the incident was even mentioned in the House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the Bicameralism, upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by Life peer, appointment, Hereditary peer, heredity or Lords Spiritual, official function. Like the ...

, by the Prime Minister Lord Salisbury

Robert Arthur Talbot Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury (; 3 February 183022 August 1903) was a British statesman and Conservative politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom three times for a total of over thirteen y ...

.

With the man-eater threat eliminated, the workforce returned and the Tsavo railway bridge was completed on 7 February 1899. Although the rails were destroyed by German soldiers during the First World War, the stone foundations were left standing and the bridge was subsequently repaired. The workers, who in earlier months had all but threatened to kill him, presented Patterson with a silver bowl in appreciation for the risks he had undertaken on their behalf, with the following inscription:

Patterson considered the bowl to be his most highly prized and hardest won trophy.

In 1907, he published his first book, ''The Man-eaters of Tsavo

''The Man-Eaters of Tsavo'' is a semi-autobiographical book written by British soldier and author John Henry Patterson. Published in 1907, it recounts his experiences in East Africa while supervising the construction of a railroad bridge over the ...

'', which documented his adventures during his time there. It was the basis for three films; ''Bwana Devil

''Bwana Devil'' is a 1952 American adventure B movie written, directed, and produced by Arch Oboler, and starring Robert Stack, Barbara Britton, and Nigel Bruce. ''Bwana Devil'' is based on the true story of the Tsavo maneaters and filmed wit ...

'' (1953), ''Killers of Kilimanjaro

''Killers of Kilimanjaro'' is a 1959 British CinemaScope adventure film directed by Richard Thorpe and starring Robert Taylor, Anthony Newley, Anne Aubrey and Donald Pleasence for Warwick Films.

The film was originally known as ''Adamson of A ...

'' (1959) and the 1996 Paramount Pictures

Paramount Pictures Corporation is an American film and television production company, production and Distribution (marketing), distribution company and the main namesake division of Paramount Global (formerly ViacomCBS). It is the fifth-oldes ...

film, ''The Ghost and the Darkness

''The Ghost and the Darkness'' is a 1996 American historical adventure film directed by Stephen Hopkins and starring Val Kilmer and Michael Douglas. The screenplay, written by William Goldman, is a fictionalized account of the Tsavo man-eaters, ...

'', starring Val Kilmer

Val Edward Kilmer (born December 31, 1959) is an American actor. Originally a stage actor, Kilmer found fame after appearances in comedy films, starting with ''Top Secret!'' (1984) and ''Real Genius'' (1985), as well as the military action film ...

(as Patterson) and Michael Douglas

Michael Kirk Douglas (born September 25, 1944) is an American actor and film producer. He has received numerous accolades, including two Academy Awards, five Golden Globe Awards, a Primetime Emmy Award, the Cecil B. DeMille Award, and the AF ...

(as the fictional character "Remington").

In 1924, after speaking at the Field Museum of Natural History

The Field Museum of Natural History (FMNH), also known as The Field Museum, is a natural history museum in Chicago, Illinois, and is one of the largest such museums in the world. The museum is popular for the size and quality of its educational ...

in Chicago, Illinois

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

, Patterson agreed to sell the Tsavo lion skins and skulls to the museum for the then sizeable sum of $5,000. The lion skins were then stuffed and are now on permanent display along with the original skulls. The reconstructed lions are actually smaller than their original size, due to their skins' having been trimmed for use as trophy rugs in Patterson's house.

Eland discovery

In 1906, Patterson returned to the Tsavo area for a hunting trip. During the trip, he shot an eland, which he noted possessed different features from elands in Southern Africa, where the species was first recognized. On returning to England, Patterson had the head of the eland mounted, where it was seen by

In 1906, Patterson returned to the Tsavo area for a hunting trip. During the trip, he shot an eland, which he noted possessed different features from elands in Southern Africa, where the species was first recognized. On returning to England, Patterson had the head of the eland mounted, where it was seen by Richard Lydekker

Richard Lydekker (; 25 July 1849 – 16 April 1915) was an English naturalist, geologist and writer of numerous books on natural history.

Biography

Richard Lydekker was born at Tavistock Square in London. His father was Gerard Wolfe Lydekker, ...

, a member of the faculty of the British Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

. Lydekker identified Patterson's trophy as a new subspecies

In biological classification, subspecies is a rank below species, used for populations that live in different areas and vary in size, shape, or other physical characteristics (morphology), but that can successfully interbreed. Not all species ...

of eland, which Lydekker named ''Taurotragus oryx pattersonianius''.

Game warden and Blyth

Colonial SecretaryLord Elgin

Earl of Elgin is a title in the Peerage of Scotland, created in 1633 for Thomas Bruce, 3rd Lord Kinloss. He was later created Baron Bruce, of Whorlton in the County of York, in the Peerage of England on 30 July 1641. The Earl of Elgin is the ...

appointed Colonel Patterson to the post of Game Warden – that is, superintendent of game reserve

A game reserve (also known as a wildlife preserve or a game park) is a large area of land where wild animals live safely or are hunted in a controlled way for sport. If hunting is prohibited, a game reserve may be considered a nature reserve; ...

s in the East Africa Protectorate

East Africa Protectorate (also known as British East Africa) was an area in the African Great Lakes occupying roughly the same terrain as present-day Kenya from the Indian Ocean inland to the border with Uganda in the west. Controlled by Britai ...

, an experience he recounts in his second book, ''In the Grip of Nyika'' (1909).

While on a safari with Audley Blyth, a son of James Blyth, 1st Baron Blyth

James Blyth, Baron Blyth ( ; 10 September 1841 – 8 September 1925), known as "Sir James Blyth, 1st Baronet" from 1895 to 1907, was a British businessman and liberal party supporter.

Blyth was the son of James Blyth and his wife Caroline, daughte ...

, and Blyth's wife Ethel, Patterson's reputation was tarnished by Blyth's death by a gunshot wound (possible suicide – exact circumstances unknown). Witnesses confirmed that Patterson was not in Blyth's tent when the shooting took place, and that it was in fact Blyth's wife who was with him at the time, as she was reported as having run screaming from the tent immediately following the shooting. Patterson had Blyth buried in the wilderness and then insisted on continuing the expedition instead of returning to the nearest post to report the incident.

Shortly after, in poor health, Patterson returned to England with Mrs Blyth amid rumours of murder and an affair. Although he was never officially charged or censured, this incident followed him for years after in British society and in the army. His case was raised in Parliament in April 1909. The incident was referenced in the film ''The Macomber Affair

''The Macomber Affair'' is a 1947 film directed by Zoltan Korda and distributed by United Artists. Set in British East Africa, its plot concerns a fatal love triangle involving a frustrated wife, a weak husband, and the professional hunter who co ...

'' (1947), which was based on Ernest Hemingway

Ernest Miller Hemingway (July 21, 1899 – July 2, 1961) was an American novelist, short-story writer, and journalist. His economical and understated style—which he termed the iceberg theory—had a strong influence on 20th-century fic ...

's ''The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber

"The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber" is a short story by Ernest Hemingway. Set in Africa, it was published in the September 1936 issue of ''Cosmopolitan'' magazine concurrently with " The Snows of Kilimanjaro". The story was eventually adap ...

'' (1936).

War service

Second Boer War

Patterson joined the Essex Imperial Yeomanry for theSecond Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the Sout ...

(1899–1902), and served with the 20th Battalion, Imperial Yeomanry

The Imperial Yeomanry was a volunteer mounted force of the British Army that mainly saw action during the Second Boer War. Created on 2 January 1900, the force was initially recruited from the middle classes and traditional yeomanry sources, but su ...

, for which he was awarded the Distinguished Service Order in November 1900. He returned home, but was again called for service when on 17 January 1902 he was appointed to command the 33rd Battalion, Imperial Yeomanry, with the temporary rank of lieutenant-colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colonel. ...

. The battalion left Southampton

Southampton () is a port city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. It is located approximately south-west of London and west of Portsmouth. The city forms part of the South Hampshire built-up area, which also covers Po ...

on SS ''Assaye'' in May 1902, arriving in South Africa after the war had ended with the Peace of Vereeniging

The Treaty of Vereeniging was a peace treaty, signed on 31 May 1902, that ended the Second Boer War between the South African Republic and the Orange Free State, on the one side, and the United Kingdom on the other.

This settlement provided f ...

.

Ulster Volunteer Force

Colonel Patterson commanded the West Belfast regiment of theUlster Volunteers

The Ulster Volunteers was an Irish unionist, loyalist paramilitary organisation founded in 1912 to block domestic self-government ("Home Rule") for Ireland, which was then part of the United Kingdom. The Ulster Volunteers were based in the ...

during the Home Rule Crisis

The Home Rule Crisis was a political and military crisis in the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland that followed the introduction of the Third Home Rule Bill in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom in 1912. Unionists in Ulster, d ...

of 1913–14. The Ulster Volunteers was a Unionist militia founded in 1912 to prevent Irish Home Rule

Home rule is government of a colony, dependent country, or region by its own citizens. It is thus the power of a part (administrative division) of a state or an external dependent country to exercise such of the state's powers of governance wit ...

. The Ulster Volunteers were based in the northern province

A province is almost always an administrative division within a country or sovereign state, state. The term derives from the ancient Roman ''Roman province, provincia'', which was the major territorial and administrative unit of the Roman Empire ...

of Ulster

Ulster (; ga, Ulaidh or ''Cúige Uladh'' ; sco, label= Ulster Scots, Ulstèr or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional Irish provinces. It is made up of nine counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United King ...

, with most of the organisation's 90,000 members coming from what is today Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is variously described as a country, province or region. Nort ...

. Many Ulster Protestants

Ulster Protestants ( ga, Protastúnaigh Ultach) are an ethnoreligious group in the Irish province of Ulster, where they make up about 43.5% of the population. Most Ulster Protestants are descendants of settlers who arrived from Britain in the ...

feared being governed by an Irish Catholic

Irish Catholics are an ethnoreligious group native to Ireland whose members are both Catholic and Irish. They have a large diaspora, which includes over 36 million American citizens and over 14 million British citizens (a quarter of the British ...

-majority parliament in Dublin. In 1913, the militias were organised into the 'Ulster Volunteer Force' (UVF) and vowed to resist any attempts by the British Government to impose Home Rule on Ulster.

In April 1914, the UVF smuggled 20,000 rifles and 2,000,000 rounds of ammunition into Ulster from Germany. Colonel Patterson is believed to have been part of this operation with some of the weapons being stored at Fernhill House, HQ of the West Belfast regiment.

The Home Rule Crisis was halted by the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914.

First World War

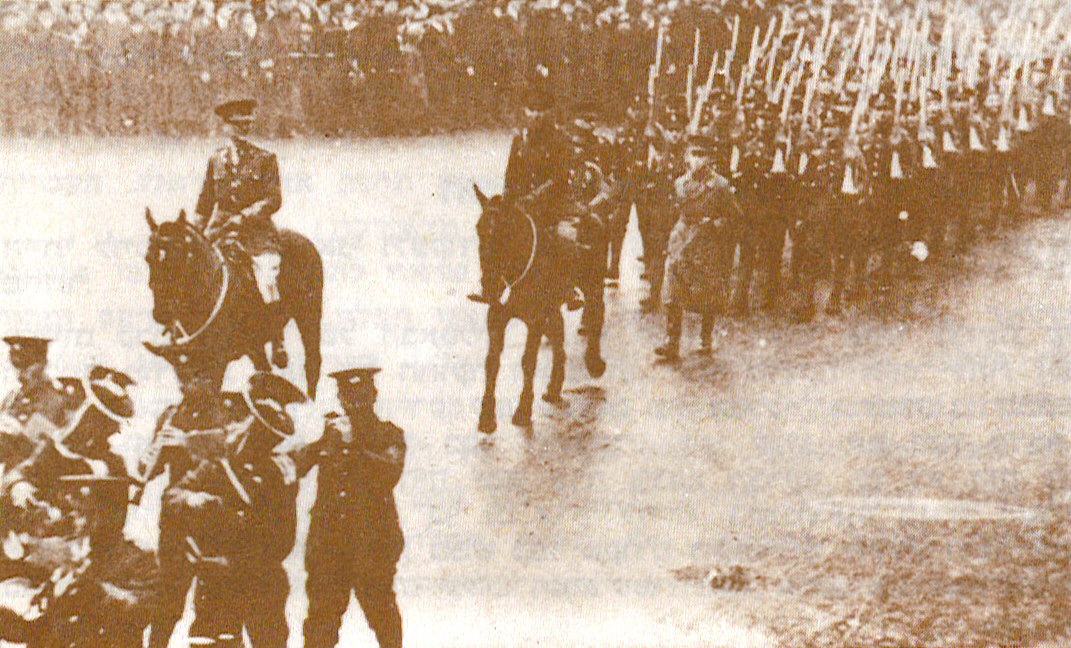

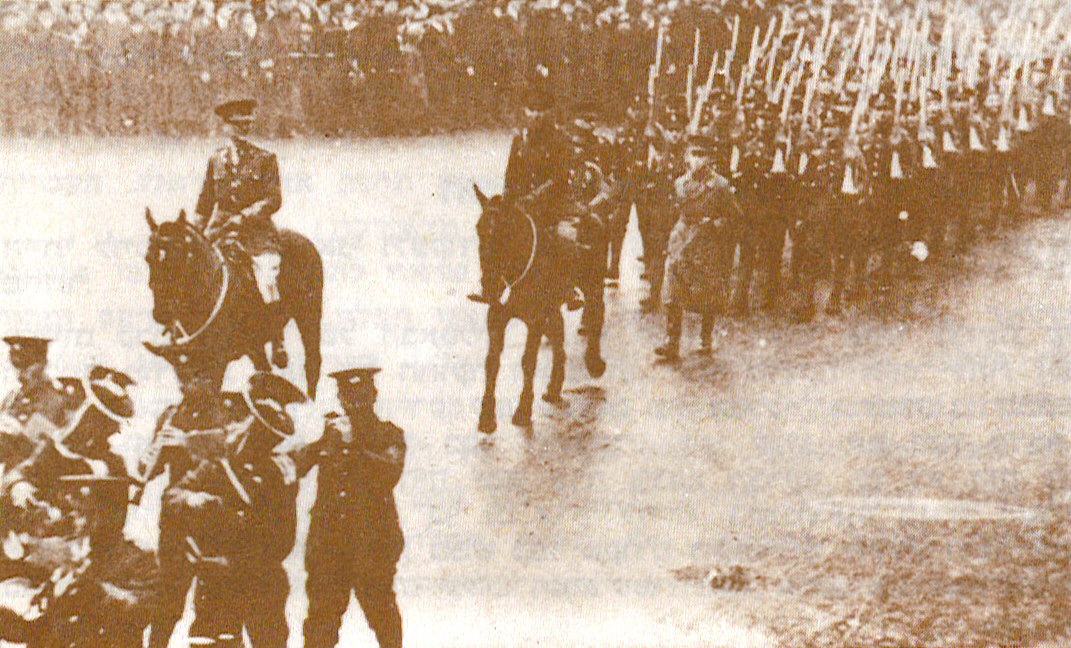

Patterson served in theFirst World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. Although he was himself a Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

, he became a major figure in Zionism

Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת ''Tsiyyonut'' after ''Zion'') is a Nationalism, nationalist movement that espouses the establishment of, and support for a homeland for the Jewish people centered in the area roughly corresponding to what is ...

as the commander of both the Zion Mule Corps

The Jewish Legion (1917–1921) is an unofficial name used to refer to five battalions of Jewish volunteers, the 38th to 42nd (Service) Battalions of the Royal Fusiliers in the British Army, raised to fight against the Ottoman Empire during ...

and later the 38th Battalion

A battalion is a military unit, typically consisting of 300 to 1,200 soldiers commanded by a lieutenant colonel, and subdivided into a number of companies (usually each commanded by a major or a captain). In some countries, battalions are ...

of the Royal Fusiliers (also known as the Jewish Legion

The Jewish Legion (1917–1921) is an unofficial name used to refer to five battalions of Jewish volunteers, the 38th to 42nd (Service) Battalions of the Royal Fusiliers in the British Army, raised to fight against the Ottoman Empire during ...

) which would eventually serve as the foundation of the Israeli Defence Force

The Israel Defense Forces (IDF; he, צְבָא הַהֲגָנָה לְיִשְׂרָאֵל , ), alternatively referred to by the Hebrew-language acronym (), is the national military of the State of Israel. It consists of three service branch ...

decades later. The Zion Mule Corps, which served with distinction in the Gallipoli Campaign has been described as "the first Jewish fighting force in nearly two millennia".

During his time in command of the Jewish Legion (which served with distinction in the Palestine Campaign), Patterson was forced to deal with extensive, ongoing

During his time in command of the Jewish Legion (which served with distinction in the Palestine Campaign), Patterson was forced to deal with extensive, ongoing anti-semitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

toward his men from many of his superiors (as well as peers and subordinates), and more than once threatened to resign his commission to bring the inappropriate treatment of his men under scrutiny. He retired from the British Army in 1920 as a lieutenant-colonel (the same rank he held when the war started) after thirty-five years of service. It is generally accepted that much of the admiration and respect of his men (and modern-day supporters) is due to the fact that he essentially sacrificed any opportunity for promotion (and his military career in general) in his efforts to ensure his men were treated fairly. His last two books, ''With the Zionists at Gallipoli'' (1916) and ''With the Judaeans in the Palestine Campaign'' (1922) are based on his experiences during these times.

Advocacy of Zionism

After his military career, Patterson continued his support ofZionism

Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת ''Tsiyyonut'' after ''Zion'') is a Nationalism, nationalist movement that espouses the establishment of, and support for a homeland for the Jewish people centered in the area roughly corresponding to what is ...

. He remained a strong advocate of justice for the Jewish people as an active member of the Bergson Group

Hillel Kook ( he, הלל קוק, 24 July 1915 –18 August 2001), also known as Peter Bergson (Hebrew: פיטר ברגסון), was a Revisionist Zionist activist and politician.

Kook led the Irgun's efforts in the United States during World ...

and a promoter of a Jewish army to fight the Nazis and to stop The Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; a ...

. He was a member of the Emergency Committee to Save the Jewish People of Europe. During the Second World War, while he was in America, the British government cut off his pension, arguing they had no way to securely transmit his funds to him. This left Patterson in severe financial difficulty. He energetically continued working toward the establishment of a separate Jewish state

In world politics, Jewish state is a characterization of Israel as the nation-state and sovereign homeland of the Jewish people.

Modern Israel came into existence on 14 May 1948 as a polity to serve as the homeland for the Jewish people. ...

in the Middle East, which became a reality with the statehood of Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

on 14 May 1948, less than a year after his death.

Patterson was close friends with many Zionist supporters and leaders, among them Ze'ev Jabotinsky

Ze'ev Jabotinsky ( he, זְאֵב זַ׳בּוֹטִינְסְקִי, ''Ze'ev Zhabotinski'';, ''Wolf Zhabotinski'' 17 October 1880 – 3 August 1940), born Vladimir Yevgenyevich Zhabotinsky, was a Russian Jewish Revisionist Zionist leade ...

and Benzion Netanyahu

Benzion Netanyahu ( he, בֶּנְצִיּוֹן נְתַנְיָהוּ, ; born Benzion Mileikowsky; March 25, 1910 – April 30, 2012)''Contemporary Authors Online'', Gale, 2009. Reproduced in Biography Resource Center. Farmington Hills, Michiga ...

. According to Benzion's younger son Benjamin Netanyahu

Benjamin "Bibi" Netanyahu (; ; born 21 October 1949) is an Israeli politician who served as the ninth prime minister of Israel from 1996 to 1999 and again from 2009 to 2021. He is currently serving as Leader of the Opposition and Chairman of ...

, who later became Prime Minister of Israel

The prime minister of Israel ( he, רֹאשׁ הַמֶּמְשָׁלָה, Rosh HaMemshala, Head of the Government, Hebrew acronym: he2, רה״מ; ar, رئيس الحكومة, ''Ra'īs al-Ḥukūma'') is the head of government and chief exec ...

, Benzion named his first son, Yonatan Netanyahu

Yonatan "Yoni" Netanyahu ( he, יונתן נתניהו; March 13, 1946 – July 4, 1976) was an American-born Israel Defense Forces (IDF) officer who commanded the elite commando unit Sayeret Matkal during Operation Entebbe, an operation to resc ...

, after Patterson. Patterson attended Yonatan Netanyahu's circumcision and gave him a silver cup engraved with the words "To my beloved godson Yonatan from Lt.-Col. John Henry Patterson".

Family

He married Frances Helena Gray in 1895. She, in 1890, had been one of the first women to take a law degree in the UK. Their son Bryan Patterson (1909–79) became a palaeontologist at the Field Museum in Chicago.Later life, death and final request

During the 1940s, Patterson and his wife, "Francie", lived in a modest home in

During the 1940s, Patterson and his wife, "Francie", lived in a modest home in La Jolla

La Jolla ( , ) is a hilly, seaside neighborhood within the city of San Diego, California, United States, occupying of curving coastline along the Pacific Ocean. The population reported in the 2010 census was 46,781.

La Jolla is surrounded on ...

, California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

. Eventually, with his wife in need of regular medical care and his own health in decline, he took up residence at the home of his friend Marion Travis in Bel Air, where he eventually died in his sleep at seventy-nine years of age. His wife died six weeks later in a San Diego

San Diego ( , ; ) is a city on the Pacific Ocean coast of Southern California located immediately adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a 2020 population of 1,386,932, it is the List of United States cities by population, eigh ...

nursing home. Both Patterson and his wife were cremated, and their ashes were interred at Angelus-Rosedale Cemetery

Angelus-Rosedale Cemetery is a cemetery in Los Angeles at 1831 West Washington Boulevard in the Pico-Union district, southwest of Downtown.

It was founded as Rosedale Cemetery in 1884, when Los Angeles had a population of approximately 28,000, o ...

, niche 952-OC in Los Angeles.

According to Patterson's grandson, Alan Patterson, one of his final wishes was that both he and his wife eventually be interred in Israel, ideally with or close to the men he commanded during the First World War. Alan Patterson, the Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation

The Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation (JASHP) is an American non-profit 501(c)(3) volunteer historical society. The society locates sites of American and Jewish historical interest and importance. It works with local community org ...

, Canadian representative Todd Young, Beit HaGedudim (the museum of the Jewish Legion), and the '' moshav'' (village) of Avihayil

Avihayil (, lit. ''Father of strength'') is a moshav in central Israel. Located to the north-east of Netanya, it falls under the jurisdiction of Hefer Valley Regional Council. In it had a population of .

Name

The moshav was named after the bio ...

(represented by Ezekiel Sivak) began a coordinated effort to honour this request in 2010. With the assistance and support of the Israeli government and Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, on 4 December 2014, the remains of Patterson and his wife, were re-interred in the Avihayil cemetery where some of the men he commanded are buried. Attending the ceremony were Prime Minister Netanyahu, members of his family, military and cabinet members of the Israeli government, the British Ambassador, the Irish Ambassador, Alan Patterson, Jerry Klinger of the Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation, Ezekiel Sivak of Avihayil, representatives and descendent family members of the Jewish Legion, Christians supporters of Israel, 350 guests and numerous other dignitaries.

Netanyahu referred to Patterson as "the godfather of the Israeli army" and "a great friend of our people, a great champion of Zionism and a great believer in the Jewish State and the Jewish people... I feel it is an obligation of our people, our State and mine personally to fulfil his testimony".

A souvenir plate postal stamp was issued by the Israel Philatelic Service in Patterson's honour./ref>

Works

* ''The Man-eaters of Tsavo and Other East African Adventures'' London: Macmillan and Co., 1907''In the Grip of the Nyika; Further Adventures in British East Africa''

London: Macmillan and Co., 1909

''With the Zionists in Gallipoli''

London: Hutchinson, 1916

''With the Judaeans in the Palestine Campaign''

London: Hutchinson, 1922

See also

*Tsavo Man-Eaters

The Tsavo Man-Eaters were a pair of man-eating male lions in the Tsavo region of Kenya, which were responsible for the deaths of many construction workers on the Kenya-Uganda Railway between March and December 1898. The lion pair was said t ...

* W. D. M. Bell

References

;Notes ;Bibliography * * * *Denis Brian, ''The Seven Lives of Colonel Patterson: how an Irish lion hunter led the Jewish Legion to victory'' (2008) Syracuse University Press *''The Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation'' http://www.JASHP.org *Henry R. Lew, "Patterson of Israel" (2020) Hybrid Publishers,External links

* * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Patterson, John Henry Military personnel from County Longford Irish hunters Irish writers Irish soldiers Irish soldiers in the British Army Irish Zionists Royal Fusiliers officers 1867 births 1947 deaths 19th-century Anglo-Irish people 20th-century Anglo-Irish people People from County Longford People from County Westmeath British Christian Zionists Jewish Legion City of London Yeomanry (Rough Riders) officers Essex Yeomanry officers Burials at Angelus-Rosedale Cemetery Companions of the Distinguished Service Order